Your DNA results come to Life when linked to your family tree

If you’ve received your DNA results from a genealogy DNA website, but have little or no genealogical research experience, this article provides insight into applying sound genetic genealogical principles to your DNA research to ensure you:

- accurately document your biological history in your family tree so you can

- discover what and who your DNA test is revealing to you.

Don’t you want to know how you’re connected to all of those DNA matches?

Learning about the ethnicity (estimates) of your ancestors is cool, but don’t you want to know about the life experiences that influenced the DNA that makes you You?

You and your DNA matches have something magnificent in common: You and each of your genetic matches share roots in Humanity. You’re each embodying parts of your shared grandparents’ genetic code. Neither of you would exist on Earth without the common grandparents who biologically connect you.

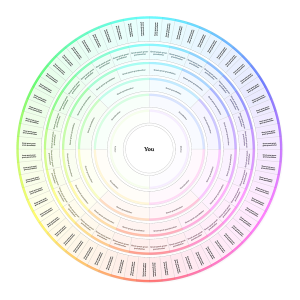

A Broader Perspective of the Human History Your DNA Reveals

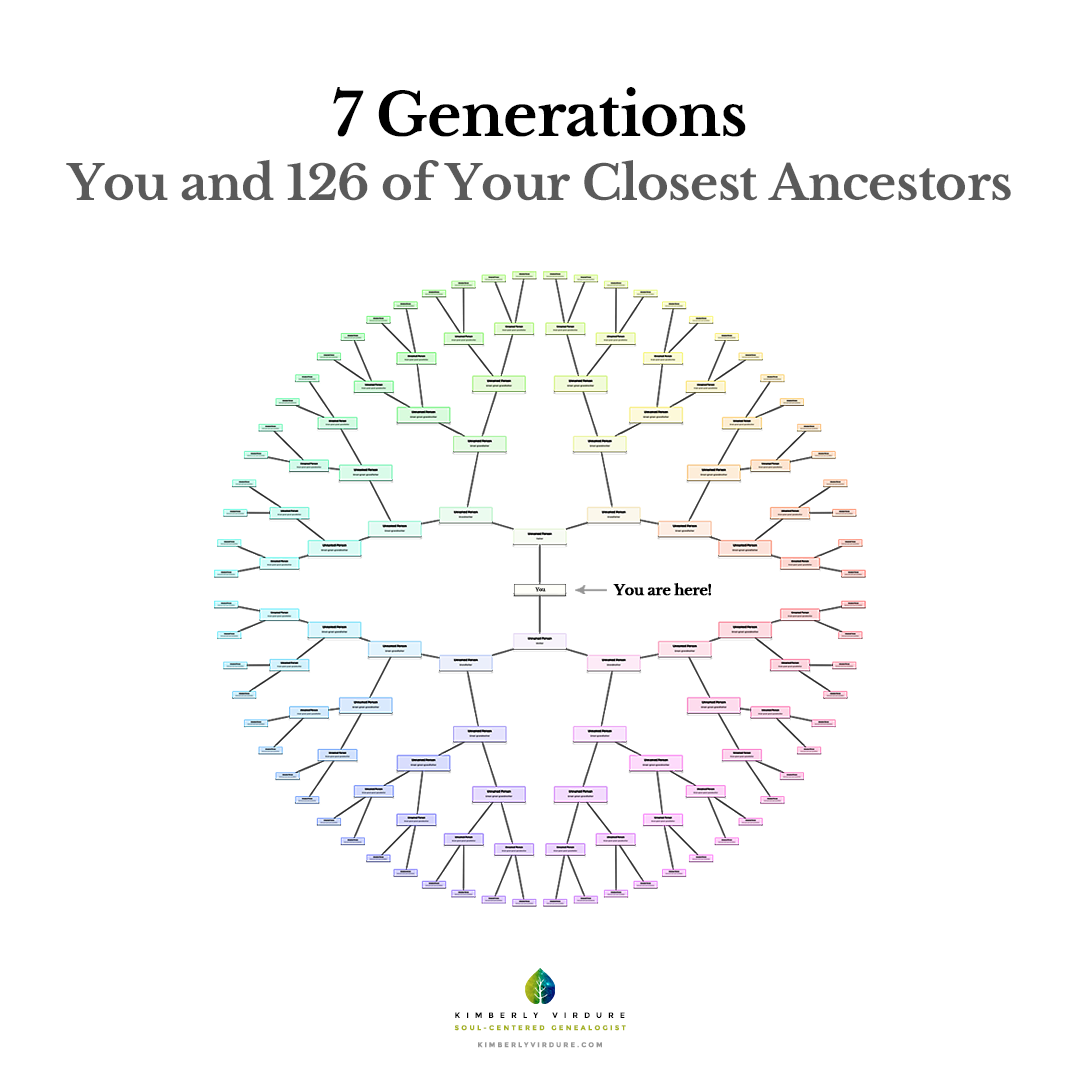

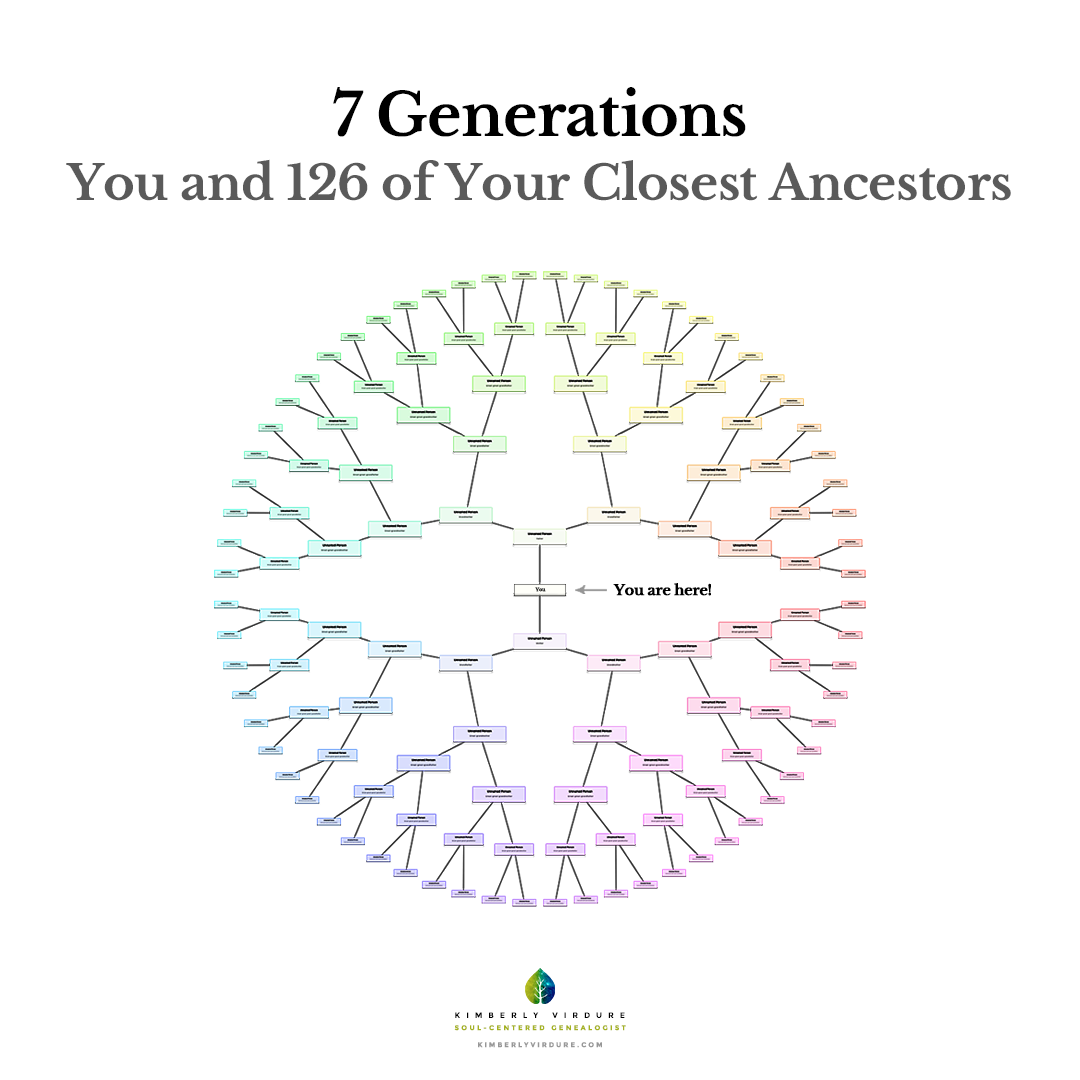

Autosomal DNA tests used at genetic and genealogy websites reveal about 7 generations of your genetic heritage (going as far back as your 5th great grandparents). Each of your DNA matches provides evidence that certainly connects you to your parents, siblings, and at least one of 124 grandparents (from your 4 grandparents, back to your 64 4th great grandparents).

Your DNA matches reveal a genetic network that spans our world and eventually connects us all. You’ll discover your relative connection to living generations – the thousands of people wandering the Earth with you today who share segments of your genetic code. Many of them are among the tens of millions who’ve submitted their DNA to various genealogy sites.

There’s no way to know your kinship to DNA Matches without a linked (and accurate) family tree.

The clues your many DNA matches represent will empower the genealogical research required to discover your true genetic lineage – if you establish an (accurate) family tree *and* link it to your DNA test results.

Who shows up as a DNA match?

Your DNA test results reveal tens of thousands of DNA matches and thousands of relatives you can potentially research.

- You, your children, and grandchildren

- Your 2 parents and all their children (your brothers and sisters)

- Your siblings’ children and their children (your nieces and nephews),

- All your grandchildren

- About 124 of your grandparents and all their children (your aunts and uncles),

- Children of your aunts and uncles (your cousins)

You can clearly see the importance of an organized research strategy based upon a clear understanding of what you want to learn from your genetic genealogy research.

Genealogy Research Tips That Make the Most of Your DNA Data

If getting your DNA tested has piqued an interest in genealogy, you can begin developing key genealogical skillsets as you discover evidence of your roots in Humanity. The following tips and resources, presented in more detail below, will help you document your true ancestral lines, and make the most of what your DNA is revealing about the individuals who’ve made your existence a reality.

- Step 1: Build a foundational family tree or review your existing tree.

- Step 2: Define your research goals. What do you want to know about your people?

- Step 3: Refine your focus by strategically prioritizing your research goals.

- Step 4: Research. Gather evidential documentation related to your research goals.

- Step 5: Analyze, correlate, and document. Thoroughly review details of artifacts gathered through research with a focus on the relationships among circumstances, events, documented facts and people related to your research goals.

Step 1

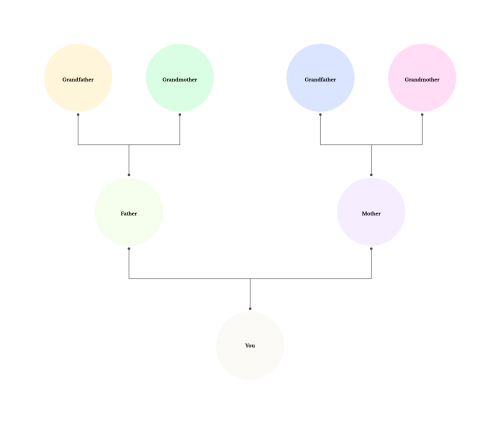

Document a Foundational Family Tree *Before* you Begin Analyzing DNA Data

It’s important to document what you know about your relatives in a family tree on your genealogical website or software of choice. This is how you’ll be able to decipher your exact kinship with your DNA matches.

If you’re just beginning your genealogical journey, just populating each entry of your family tree with the following core information is a good start:

- birth name (no maiden names),

- birth names of spouse(s), partner(s), and children.

- dates and locations of births, deaths, marriages.

If you’re unsure of any of this data, don’t guess, leave it blank (you’ll be clarifying mysteries in your research).

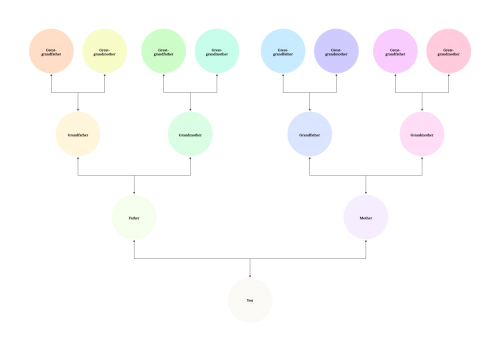

Start with you and work your way back documenting what you know about your mother’s line and your father’s line. If you already have a family tree with your parents and grandparents (on both sides) review the facts ensuring the key data listed above are accurate and complete.

Document your direct ancestors and collateral relatives on your family tree

- Your direct ancestors are your parents and all your grandparents, the ones who’ve brought you forth.

- Direct descendants are your children and grandchildren.

- Collateral relatives are blood relatives who aren’t part of your direct line of ancestors, such as siblings, aunts, uncles, and cousins.

Remember: your DNA matches point toward 124 grandparents, all their children (your aunts and uncles), and their children (your cousins). Most of your DNA matches are collateral relatives and have surnames of your biological lines and/or the married names of female relatives. This is why documenting your aunts and uncles (your cousins’ parents) and their offspring (your cousins) in your foundational family tree will help you ascertain from which of your many branches each DNA match descends.

You can read about determining cousin kinship here —> Exactly How You’re Related to Your Cousins

If you’re updating an existing family tree.

Review and clean up each relative’s entry. Closely review records and artifacts you’ve attached to each person in your family tree to reacquaint yourself with your body of research.

Have you attached original documents you never actually read?

Review the details of original documents, like census records, vital records, and photographs. You’ll probably discover new information.

Scrutinize unoriginal documents, second-hand information, and unsourced facts for each person.

Read them closely. Are the facts proven by firsthand sources? Are they hearsay? If there’s no solid evidence to support an artifact, flag it for later review and remove it from your relative’s entry. This process of questioning will lead to broader and more accurate discoveries in your research.

Step 2

Decide what you want to know about your people.

Whether you’re establishing your family tree or cleaning up an existing one, new questions will continually arise about the people, places, and relationships on your family tree. These questions form your research goals and define the scope of your genetic genealogical research.

Genealogy research begins with what’s known, then builds upon existing documented facts to gather evidence of what’s currently unknown. A sound research goal poses a question based on facts and supports an evidential foundation that documents each generation’s connection to the next.

What do you want to know?

- What information is missing?

- Does anyone on your tree intrigue you?

- Is there a family mystery to be solved?

- Where’s your heart guiding you?

You’ll have an instinctual draw towards ancestors whose life story reflects yours in some way. These are the relatives who often embody the emotional, physical, intellectual, and/or material legacies you’re directly evolving through your experience of life. Following a pull toward researching a particular ancestor will prove to be enlightening and most interesting.

Document Clear and Specific Genealogical Research Goals

Trying to remember what you want to know about who while you research yields disjointed results (and false entries) on your family tree. Keep a written or digital record of questions that define your research goals. Organize your goals by ancestral lines, surnames, or whatever works for you. This frees your mind from the task of remembering. Update and refine your research queries as you go along.

Examples of focused genealogical research goals

- Some research goals are relatively straight-forward, such as: Where was my maternal grandmother born?

- Others may be more complex to resolve, like: What circumstances surrounded the disappearance of my paternal great-grandfather in 1923?

- Some may be relatively easy to solve, but carry a heavy emotional charge, like: Was my paternal grandmother my father’s biological mother? If not, who is my biological grandmother?

- And then there’s the inevitable question of: What’s my kinship to DNA Match XYZ?

Step 3

Develop a Research Strategy

Organize your DNA and genealogical research goals to form a coherent, synergistic strategy.

How can DNA evidence help you answer your genealogical research goals?

As you form a strategy, remember: your autosomal DNA test results are revealing your biological connection to 7 generations of your genetic heritage (going as far back as your 5th great grandparents).

Each DNA match provides evidence that certainly connects you to your parents, siblings, and at least one of 124 grandparents (your 4 grandparents, back to your 64 4th great grandparents). This is collectively more than 7, 500 years of distinct and unique human experiences.

Identify DNA Matches whom you know are biologically tied to your research goals.

There’s no need to examine your relation to thousands of DNA matches. Establishing research goals will help you target specific key matches. As you determine your relation to key matches, others will logically fall into their place on your tree.

Prioritize your research goals.

Align your research goals with the objective of building upon the foundational tree you established in Step 1.

The overall goal is to systematically document more recent generations first. Each preceding generation will often (not always) fall into place through documented facts from the previous. Honoring this principle is vital to determining your kinship to DNA matches.

Certain research queries need to be answered before you can get to the heart of another.

If, for example, your research goal is to determine the identities of a set of 3rd Great Grandparents, but you haven’t thoroughly researched your 2nd Great Grandparent (their child), research of your more recent ancestor is a priority as clues about your 3rd Great Grands will likely be found in earthly records and genetic imprints of their child.

Of particular interest is evidential proof of your 2nd Great Grand’s legally documented parentage (such as an original death or birth certificate). The more you know about your 2nd Great Grandparent’s lifetime, the more empowered you’ll be to build upon more recent genealogical evidence as you research back in time.

Step 4

DNA and Genealogical Research

Since you established the foundation of your family tree with what you know (Step 1), are clear about what you want to know (Step 2), and have established a research strategy (Step 3) you can now begin the actual research with a laser-like focus.

DNA Match Analysis

Make the Most of DNA Tools Provided by Your Testing Company

It’s wise to review educational resources and guides published by the genetic genealogy company you’re working with.

- Ancestry DNA: https://support.ancestry.com/s/ancestrydna

- My Heritage DNA: https://education.myheritage.com/learn/dna/all/

- FamilyTree DNA: https://learn.familytreedna.com/autosomal-genealogy-matching/

Estimated Kinships through cMs

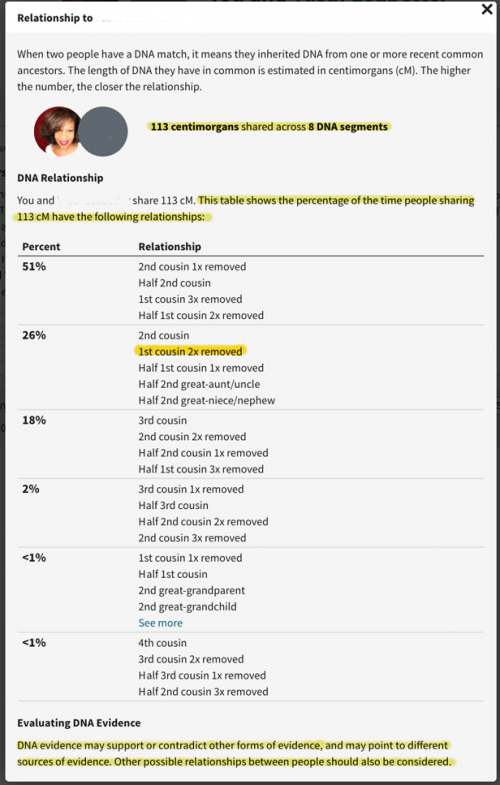

Please believe: The estimated relationships between you and your matches are definitely estimates.

DNA evidence provides clues you’ll integrate into a larger body of genealogical evidence. Estimates are more likely to be accurate the closer in relation you are to a DNA match. A DNA match with a parent is highly likely to be estimated as a parent/child relationship. A DNA match with a great grandparent is less likely to be estimated as a great grandparent. Genealogical research is required to determine actual biological connections.

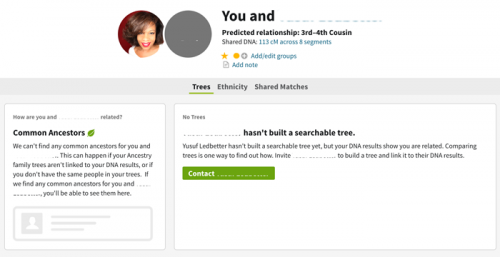

This is a key DNA match on Ancestry.com related to a (past and completed) research goal of determining the identity of my paternal Grandfather.

As you can see, this DNA match hasn’t linked a family tree, so there’s no way to determine our kinship without a documented genealogy. The predicted (or estimated) relationship is a clue – not a fact. The only DNA sample I had at the time that certainly connected me to my Grandfather was my own.

Our few shared matches were mostly treeless. One shared match has matches on my paternal and maternal lines. Another has (questionable) parentage documented on their tree that doesn’t correspond with other documented genetic and genealogical evidence.

As I initially had no way to determine our kinship, the evolution of my foundational DNA research tree (with collateral relatives) eventually revealed this matches’ place in my ancestral lines. We’re actually 1st cousins 2x removed.

Tips on how to handle mystery DNA matches and those without family trees can be found here –> How to Leverage DNA Matches without Family Trees

One Genealogy Research Goal Leads to Others

There’s another key match among our shared matches (estimated to be a 4th-6th cousin) who clearly reveals a grandparent relationship tied to the era of American slavery. Though they have a well-sourced family tree tied to their DNA profile, there are no common surnames or geographical locations documented among our trees. This is a reflection of the realities of slavery in the U.S. and calls for more in-depth research techniques to identify our common grandparents. Determining our kinship with this mystery DNA match is in my queue of research goals to be addressed in the future.

Focus on One Research Goal At a Time

Genetic genealogy research sessions can become confusing and overwhelming when pursuing multiple research goals at once. Focus on one (well defined) goal at a time so each evidential clue receives your undivided attention. This cultivates the intellectual focus you need to identify connections among people, places, and multiple artifacts – like catching how a relative’s data on a census record is clarifying questionably transcribed data on a marriage record.

Consider the realities of being human throughout your research.

When biologically accurate, the genealogies linked to your DNA matches are among the most valuable sources for genetic genealogy research. If they’re not accurate, which is frequently the case, assuming their correctness will lead your research astray and you may end up with the wrong family lines on your tree.

Be aware of fictional family trees.

Many people fall prey to research bias in favor of documenting biological connections to famous and admired people. Some family trees reflect unresolved family secrets, while others may reflect a biological untruth to protect living relatives from an emotionally charged reality. Some genealogical mysteries represent human stories that aren’t yours to reveal.

What looks right isn’t always true.

Perform your own independent research of any evidence you’re considering (including photographs) – even if an artifact looks right, or seems to make sense.

Genealogy Research

Offline Genealogical Research is Golden!

Less than 5% of all available genealogical records are available online! The most reliable and informative genealogical sources that exist are tucked away in the attics, drawers, basements, and memories of relatives and others tied to your family of interest. Think of where you might find:

- photo albums

- greeting cards

- old insurance policies

- birth and death certificates

- family bibles

- diaries and journals

- newspaper clippings

- letters and notes

- property deeds

- medical records, and

- people who knew the relatives you’re researching.

If you’re able to look at photo albums with an elder who knew those who’ve passed away, ask questions about the pictures. Capture photos of the photos, and record complete notes about who, what, when and where the photos reveal.

Learn about where your ancestors lived.

Of course, nothing tops genealogy research excursions to your ancestors’ communities. This is where you can find, see, touch and document original artifacts that cannot be found online.

Historical archives (like The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration – NARA), courthouses, universities, churches, hospitals, and libraries are just a few offline resources worth exploring. As you discover the details of where your relatives lived, what they were into, and how they interacted within their communities and our world, you’ll determine which offline research resources align with your research goals.

To find a genealogy research facility near you:

Tips for Online Genealogy Research

If available offline genealogical records have been analyzed and recorded on your tree, you’re best positioned to use what’s online to build upon what you know. It is also tremendously valuable to publish original artifacts you’ve discovered offline *with complete source citations*. This helps fellow researchers and inspires broader collaboration.

For Genealogies Rooted in the United States of America

If any of your ancestral roots are in the U.S.A. your research will reveal genealogical records that reflect American history. Deciphering genealogical artifacts and correlating relationships among people, places, and things require knowledge of historic events.

The World Digital Library (sponsored by the Library of Congress) has interactive maps and timelines that capture Human history from 8000 BCE to 2000, which of course includes the history of the United States of America from 1492 to the 20th Century.

Study Historic Maps and Learn About Ancestral Communities

As state, county, and municipal lines (and names) have shifted over time, studying maps relevant to your research goals is vital to analyzing historical records – like census and financial records.

- MapsofUs.org provides Interactive maps for each state that illustrate U.S. state and county formation over time. There are also census year maps, historic maps, and D.O.T. county road and highway maps.

- You can also study historical U.S. counties overlaid on Google Maps at randymajors.com.

- Do targeted Web searches related to counties, cities, towns, and surnames on Google Books

- Search geographies of interest and related events that impacted your research subjects at the Library of Congress

- Search for newspapers published in the communities of research subjects.

Genealogy Internet Searches

Genealogy records available at your DNA testing website provide a good start, however, there’s often much more documentation to discover across the Web.

- Use loose search terms to widen search results.

- Explore more than one repository for each of your key research subjects.

- Google your research subject’s name. Try different combinations of their names, where they lived, and years of interest.

- familysearch.org: I often find Family Search has more transcribed U.S. records than Ancestry.com.

Step 5

Analyze, Correlate, and Document Your Genetic Lines

Gathering artifacts is the easy part, and where many people stop (a key reason for the extraordinary number of inaccurate and incomplete family trees). This most important step in genealogy research requires the most time, effort, and thought.

Follow the Genealogical Proof Standard (GPS)

The Board for Certification of Genealogists (BCG) created and maintains the Genealogical Proof Standard which provides best practices for documenting ancestries as factually as possible. You’ll save yourself a lot of time and effort, and bypass a few brick walls in your research if you consistently honor the 5 components of the GPS with each research goal:

1. Reasonably exhaustive research.

2. Complete and accurate source citations.

3. Thorough analysis and correlation of evidence.

4. Resolution of conflicting evidence.

5. Soundly written conclusion based on the strongest evidence.

As stated on the BCG’s website: “The GPS overarches all of the documentation, research, and writing standards described in Genealogy Standards, and is applied across the board in all genealogical research to measure the credibility of conclusions about ancestral identities, relationships, and life events.”

Anyone can do genetic genealogy, but not everyone practices genetic genealogy.

As with any discipline, the development of genealogical skillsets requires dedicated study, application, and continuing education – over time. If you’re just beginning to research your ancestry consider learning how to apply standard genetic genealogy principles as you go to ensure you accurately document your true ancestry.

The Board for Certification of Genealogists (BCG) provides several sources for learning genealogy and genetic genealogy on their website. These educational resources include self-directed, collaborative study, and formal education channels.

Genealogy isn’t for everyone.

If you discover you’re just not inspired to learn and practice genetic genealogy, but you want to know your ancestry, get some help with documenting your place in human history.

Every Life Represents a Sacred Human Experience

Genetic and genealogical research introduces you to thousands of individual human lifetimes that echo aspects of your experience of being You. Considering each relative’s humanity throughout your research reveals far more than ethnicities, countries of origin, and individual identities.

As you research, remember: human lives are complex.

Like you, each individual you research represents a unique expression of the Human experience that’s deserving of thorough review and consideration. Keep your research organized, goals focused, and mind open so that you capture their lives as accurately as possible. And please don’t skip any of these steps:

- Step 1: Build a foundational family tree or review your existing tree.

- Step 2: Define your research goals. What do you want to know about your people?

- Step 3: Refine your focus by strategically prioritizing your research goals.

- Step 4: Research. Gather evidential documentation related to your research goals.

- Step 5: Analyze, correlate, and document. Thoroughly review details of artifacts gathered through research with a focus on the relationships among circumstances, events, documented facts and people related to your research goals.

Soul Centered

DNA Discoveries

Are you stuck or overwhelmed in your DNA research?

If you need help researching your connections to DNA Matches, let’s meet (by phone or video) to discuss ways I can help you discover and document your kinship with Humanity.

Leave a Comment